.webp)

.webp)

:format(jpg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/coindesk/QPFXGSRWGNDX5IEREJ34PT5OKI.jpg)

Dan Larimer who led the EOS’s $4 billion token sale in 2017, one of the largest of the ICO era.

At Consensus 2023, a few CoinDesk staffers came together for a panel reflecting on major events in crypto history. When we were polled on the most important of these big moments, the plurality of votes went to what might seem an odd choice – the chaotic, fraud-filled period of “ICO mania” spanning from early 2017 to mid-2018.

That’s not an obvious choice, because these “initial coin offerings” (ICOs) were not unambiguously a Good Thing. Many of the downsides and threats they brought into crypto have remained big problems – problems like investment fraud and securities violations. One retrospective study found that80% of all ICOs during the boom were outright scams.

But there was a lot more going on than grifting and rug pulls. Some of the most important projects in present-day decentralized finance launched as part of the ICO bubble, including key pillars like Aave and 0x. Speculators who were informed, careful and very lucky could have walked away with serious returns based on backing real, productive projects.

And the historical significance of the ICO boom goes far beyond the relative handful of actual winners who got funded. Most importantly, if you were one of those informed, careful and lucky investors, you were able to profit from your insights regardless of your geographic location or citizenship. ICOs fulfilled crypto’s promise of cutting out financial middlemen – in this case, the venture capitalists and investment bankers who have long dictated the terms of startup investing.

“Looking back on that period, we were building infrastructure,” says one prominent speculator who first dallied with crypto during the ICO era and went on to work in crypto trading professionally. “You can’t build something, and build the [underlying] infrastructure at the same time. I think of all that as trial runs.”

An ICO at the time looked a good deal like an initial public offering in equities markets (and they still do). From a buyer’s perspective, the main difference is that they’re accessible to any individual who can set up a digital wallet and fund it with a smart contract token like ETH, SOL, or ATOM.

But there are major differences between what investors in ICOs and IPOs are actually buying. An IPO buyer gets a legal claim on a portion of a company. An ICO buyer gets tokens – and that’s all. Tokens do not formally represent any ownership in a company. While IPO investment gains are premised on growing corporate revenues, ICO tokens only rise in value because people want to use them. Broadly, this is the “utility token” thesis that was believed by some to separate token sales from securities offerings.

That’s why I, and many others, at the time felt the designation“ICO,” so close to “IPO,”would obscure what makes ICOs and tokens unique, especially in the eyes of regulators. Five years later, with a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) crackdown ongoing, the nomenclature indeed seems foolhardy.

Because there really is an argument that “utility tokens” are not securities – it’s just an argument that has been abused into almost unrecognizable shape. ICO tokens were intended to grow in value, not because they represented a claim on revenue on a common enterprise, but based on the arguments inJoel Monegro’s “Fat Protocols” thesis(Monegro is a prominent VC with Union Square Ventures). Very roughly, the argument is that tokens issued to fund the creation of a decentralized service would also be required to access that service, and gain value based on the demand for it – but such demand would be driven as much by a broad ecosystem as by any particular designer or administrator.

Would-be ICO investors could read a white paper for a proposed tokenized project, and decide whether the idea seemed to fit this model. They might also examine whether the founders seemed trustworthy. And because public smart-contract blockchain platforms like Ethereum were and are universally accessible and uncensorable, buyers didn’t have to be wealthyaccredited investorsto put money into good deals.

But while on-chain anonymity and universal access blew a hole in the fortress of venture investing, they also made some basic due-diligence processes unreliable or impossible. Far more than even during the 2021 crypto boom, transparency during the ICO craze was severely lacking; anonymous founders could easily steal investor funds; and hype often overshadowed any rational approach to evaluating proposed services.

The ICO era was, by most objective measures, a disaster for investors and a huge waste of capital for crypto. But it remains endlessly fascinating – and perhaps not as much of a catastrophe as might appear.

It’s hard to nail down a clear starting point for the “ICO era,” but one signpost might be with the $60 millionfailure of The DAOin 2016. That decentralized organization was intended to act as a collectively managed investment fund for Ethereum-based projects, with a balance of power that privileged major holders.

That project’s investing model balanced the input of experienced large investors with that of less expert funders. As The DAO co-founder Cristoph Jentzch recently put it to me, that model could have bent the whole ecosystem towards deeper, more expert vetting of proposed projects. It might still be the right way to balance the expertise of traditional venture capitalists with the open nature of DeFi.

But The DAO was catastrophically hacked before it could launch, resulting in an extended state of emergency for Ethereum as a whole. Meanwhile, projects that had expected to take funding from The DAO were left high and dry, searching for an alternative model.

For better or worse, that model was close at hand. Ethereum’s token presale, conducted in 2014, became a powerful vehicle (it raised$2.2 million in 12 hours). By the time Ethereum launched in 2016, it had proven not only that a token sale could fund the development of important projects, but that it could make early investors rich.

But the true madness of the ICO era wouldn’t be unleashed until the introduction of the ERC-20 token standard. The standard lays out specific features that ensure tokens operate uniformly across the Ethereum ecosystem, including external tools like wallets and exchange APIs. It was first introduced as early as 2015, though not fully formalized untilSeptember of 2017.

Creating ERC-20s was and remains far less technically and socially challenging than launching a new “layer 1” blockchain. Instead of having to recruit its own miners or validators, a project could rely on the existing security of the Ethereum blockchain. On the other side of the market, ERC-20s were far less technically challenging than standalone blockchains to integrate into exchanges, wallets and other services. It was during the ICO boom that the benefits of smooth interoperability really became clear.

“People started to [adopt] the shipping container worldview,” says our anonymous trader. “Which is that, if these things fit in the same [ERC-20] container, it’s much more efficient.”

There were unquestionably some huge successes to emerge from the ICO era. Near the top of that list are Aave (AAVE), Filecoin (FIL) and Cosmos (ATOM). Each is a substantial part of the blockchain ecosystem nearly six years after their initial fundraising push, and have generated huge returns for ICO investors.

Another project that emerged from an ICO to produce an actual successful product is Brendan Eich’s Brave Browser, which raised $35 million worth of ETH when itICO’d in 2017, and has continued to build since. The BAT token that provides various services through the browser certainly hasn’t mooned, but it has largely held value against broader crypto indices.

But those positive examples must be cherry-picked from a much bleaker big picture dominated by fraud, theft and failure. The takeaway seems to be that ICOs can be very effective fundraising tools in individual cases where founders are trustworthy and well-intentioned, but that overall they invite massive fraud.

The libertarian ideal of a completely unregulated financial market, in short, did not quite deliver on its promises, in what was arguably the biggest controlled economic test of the idea in modern history.

A large amount of ICO investment proved unproductive because investors themselves didn’t understand the novel financial and technical theory that made tokens investable. The “fat protocols” thesis fundamentally only makes sense if a protocol or contract’s function is truly native to or tightly integrated with its token. Good examples include ether’s role as “gas” for Ethereum transactions, or filecoin’s use to pay for verifiable on-network storage. These use cases make sense because they leverage the three blockchain pillars of decentralization, open access and trustlessness.

But the further you get off-chain with any feature of a distributed ledger, the more this model breaks down, for at least two reasons. First, because there’s less and less on-chain verification that goods or services are actually being provided, inviting fraud. This was seen repeatedly in scam ICOs, where entrepreneurs claimed their tokens were “backed” by real estate or diamonds – claims that couldn’t even be verified, much less redeemed, on-chain.

Similarly, “fat protocols” can’t hold when there’s no *exclusivity* to the relationship between a token and a service. You can’t use anything but ETH to run smart contracts on Ethereum, so ETH has economic value. But you can take your pick of currencies to pay a dentist, sodentacoin(a “blockchain solution for the global dental industry”) doesn’t have economic value.

Investors missing these fundamentals enabled a huge amount of low-IQ mis-investment and fraud. And we’ve seen it continue into the present day, such as with various “exchange tokens.” There is no rational investment thesis for a nominally decentralized token attached to a fully centralized exchange, yet traders treat tokens like Binance Coin and FTX’s FTT as similar to equity.

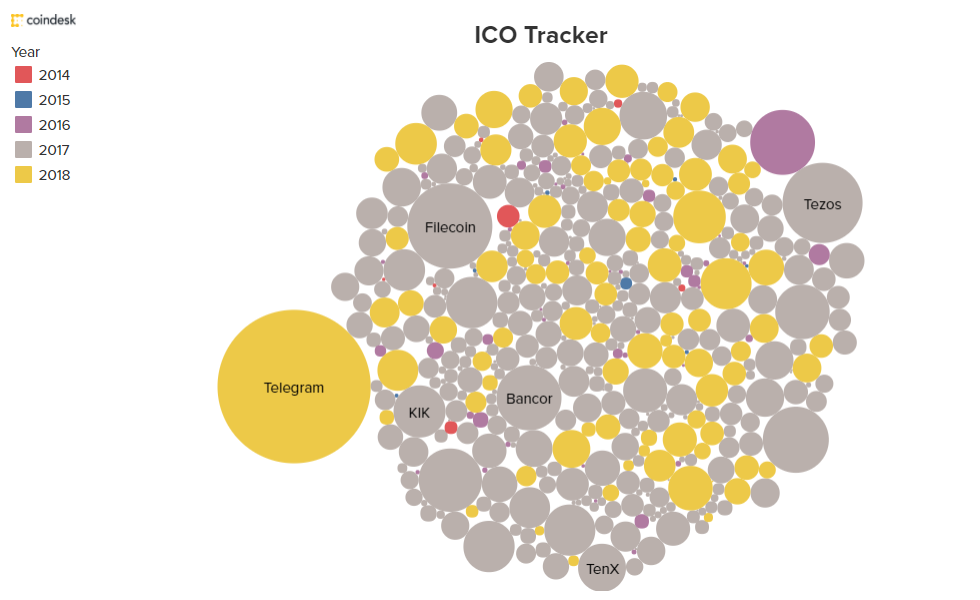

A graphic from ICO Tracker showing the largest ICOs of the ICO boom.

A graphic from ICO Tracker showing the largest ICOs of the ICO boom.But even for those with full comprehension and the best of intentions, ICOs had major downsides. The capital structure, which often led to startups getting huge blocks of cash up front, remains its most profound drawback. If you raise several hundred million dollars to start a project, you no longer have much incentive to actually build it.

“If you were a builder then, you had a choice,” says our ICO veteran. “You could cash in quick with bananacoin, or you could go start something like Maker or ENS and work hard for years and make a lot more money.”

Further, the necessity of high-stakes treasury management was basically detrimental. Most ICOs raised in ETH, which crashed dramatically in dollar terms soon after the ICO bubble died down. So when it came time to actually operate, the U.S. dollars available to hire developers and pay for offices were far fewer than the initial headline fundraising number might have suggested.

At the same time, the temptation of speculating with ICO funds was too much for some founders. A project called Substratum was found in 2018 to beactively trading with its treasury, with a full-time trader on staff. (Substratum is no longer active, but it at least seems to have been a legitimate project. It was reportedly acquired in 2021 by Epik, a domain registrar, and the token now trades at basically zero.)

Even happy versions of this story conceal this shadowy underbelly: A successful startup called Monolith, for example, managed to turn a $16 million raise into $25 million using a DeFi-basedhedging and leverage strategy. The problem here, even leaving aside hidden risks, is that this activity meant time-and-effort not spent developing the actual product pitched to investors.

Here we see just one way 2017 ICOs created a misalignment of interests. Because they exist outside of any real legal framework, ICO tokens didn’t give investors any direct exposure to the upside of treasury speculation. Holders benefit if a project is finished and finds real users (or if investors can find a “greater fool” to sell their tokens to in the meantime). Building is obviously easier with 50% more funds, but there’s no true, enforceable obligation to actually spend those funds on the project.

On the other hand, major treasury *losses* are almost guaranteed to harm investors by slowing or stopping development. And those are infinitely more likely if a project is gambling with its own funds.

It’s impossible to pinpoint a real “end” for the ICO era, because while they’re less visible in the U.S. and similar jurisdictions now, theystill happen frequently. But one kind of end to the ICO era can be marked to the moment existing large companies tried to get in on the action – and hit a brick wall.

Most notably, Telegram’s plan to tokenize the network and sell a TON token was a technically defensible idea that might have been transformative, butserious pressure from the SEC in 2019led to its cancellation. Also in 2019,the SEC sued messaging platform Kikfor its 2017 token sale, eventually leading to a $5 million settlement.

I would nominate a less obvious 2019 event as also marking the end of the ICO Era: Facebook’s proposal of theLibra stablecoin. Libra likely would not have been issued or sold as an ICO. But as the highest regulatory and legal bodies in the U.S. scrutinized it, their blunt hostility made clear that they were horrified by Facebook’s adoption of norms and practices that had become standard in crypto. The regulatory backlash we’re facing five years later still seems fueled by that incredulous outrage.

There may someday be a regulatory regime that successfully imposes good transparency and controls on ICOs while retaining their advantages of accessibility. But that’s likely many years, or even decades, away. In the meantime, though, is there a way to bend the moral arc of token launches towards rationality and honesty?

It can be difficult not to regard those who lose money on ICOs cynically. Many ICOs were and are so obviously scammy that it can be hard to feel bad for people who fall for them. That’s especially true because so many token traders are self-described degens and gamblers.

But free market economic theory sees a longer-term upside. A true Wild West like the ICO scene can be seen as a process of education and hardening, with every loss a lesson. It is the precise opposite of the infinite-bailout mentality that people fear in the current mainstream banking environment. Over time, in theory, it should make participating individuals much smarter investors, ultimately leading to a “safer” market than any regulation could impose – at least after a sufficient period of hard lessons.

That, at least, is the theory. ICOs are the financial equivalent of Darwinian evolution, slowly weeding out both fraudulent founders and uninformed speculators. Maybe the carnage of the ICO era made traders smarter. Maybe over time, this radically free transnational investment market will become a global positive for humanity.

.png)